As I sit down to write this blog on my final read for 2025, I’m struck by how fitting it feels that this year is ending with this book. ‘Rest’ dismantles one of the most deeply held beliefs of our time – that our value is measured by how much we work. And ‘resting’ means doing nothing.

Rest

Why You Get More Done When You Work Less

by

Alex Soojung-Kim Pang

If you are the kind of person who is looking to evolve through this lifetime you have been given, then these 247 pages (excluding a very well written preface and acknowledgments + bibliography) should be a part of your ‘to-read’ list in 2026. If you are not looking to evolve, then anyway you won’t have a ‘to-read’ list!

The Beliefs We Inherited About Work (and Rest)

Pang explains that our obsession with constant work and the belief that long hours equal seriousness, and success – took root during the Industrial Revolution, when human beings were expected to function like machines. And before we begin to understand what ‘resting’ means and the impact it can have on the quality of our lives, we need to first dismantle this notion of work as understood traditionally.

“Rediscovering the importance of rest, though, requires rejecting our modern collective delusion that work is the central measure of our value… It’s a myth that arose during the Industrial revolution.

The template of industrial labor, including its underlying assumptions about work and rest, was copied by service industries, professions, and bureaucracies in the mid-nineteenth century. The modern office was conceptualized as a machine for rationalizing and organizing intellectual labor.”

The same assumptions about work and rest were copied wholesale, long after the factory floor disappeared. Who does this system really serve? Do explore this argument with someone in your circle with intellectual curiosity over a nice dinner.

If you, like me, have been a part of the corporate culture at some point – then work-life balance cannot be a new term. The underlying idea there implicitly validates the concept of “work and life as Manichaean opposites, perpetually in conflict. As a result, we see work and rest as binaries. Even more problematic, we think of rest as simply the absence of work, not as something that stands on its own or has its own qualities.”

It is also very interesting how we inherited only the notion of work from the Industrial age – and not the emotions or social context associated with it.

“Only in recent history has “working hard” signaled pride rather than shame.”

The Notion of Productivity at Work

I really debated whether I should add this section to the blog. Primarily because I am not sure if I fully agree with the universality of the idea that long hours don’t always mean better output.

But it is somewhat true that in many modern workplaces, visibility replaces effectiveness. So ‘being busy’ becomes a performance, then that is definitely counterproductive. That kind of culture creeps in quietly and is usually really hard to unwind. An obsession around productivity rather than product design & enhancements usually signals a lack of imagination at the top. Reduction in workforce is then a lever that’s pulled as a reactionary cost measure to improve bottom line by leaders who don’t have better or original ideas.

Research repeatedly shows that “..companies that put profits first are more likely to lose money than those that treat profit as a by product of doing great work.”

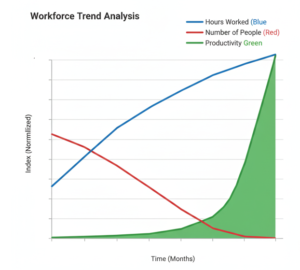

Apparently, productivity rose dramatically through the twentieth century—and economists fully expected working hours to decline alongside it. They did… until the 1970s. Then, despite continued gains in productivity, hours stopped shrinking.

So Where Do Ideas Actually Come From?

The book explores one very interesting question that I had never before thought of: Where do ideas come from?

Apparently, science has not yet managed to explain how creativity actually works. However, research is ongoing, and neuroscience does support one theory.

“One striking characteristic of the brain in its resting state is that its barely less energetic than the engaged brain.”

The book explains the role of “DMN or default mode network.. which are a series of interconnected sections that activate (in the brain) as soon as people stop concentrating on external tasks, and shift from outward focused to inward focused cognition.”

And that “DMNs of people who score high on creativity tests differ from those of people who are average.”

Another aspect of research that the book explores is what we commonly call mind-wandering or “task-unrelated thinking,.. (where) your mind naturally wanders when you are doing something that’s automatic or involves muscle memory, like folding clothes or driving down a familiar road…” and shows evidence why this might stimulate creativity.

One of the most insightful parts of the book is where the author explores how creative breakthroughs happen when you are working on a problem. While preparation and verification stages both require conscious attention, the final phase of “illumination” will arrive only if you don’t force it.

“Instead you have to trust that your unconscious will drive to (that) phase, illumination, the moment when the answer bursts into your consciousness.” Where it feels like the answer “occur(s) suddenly, without exertion, like an inspiration.”

So the author doesn’t romanticize inspiration, but he also doesn’t reduce it to grind. Ideas, he suggests, often arrive from places we don’t control—they are “slumbering in the unconscious”. I absolutely loved that expression.

“These philosophical arguments might seem arcane, but the assumptions that knowledge is produced rather than discovered or revealed, that the amount of work that goes into an idea determines its importance and that the creation of ideas can be organized and institutionalized, all guide our thinking about work today.”

“In other words, it is not constant effort that delivers results but a kind of constant, patient, unhurried focus that organizes attention when at work and is present but watchful during periods of ease.”

So if you want to have better ideas, build in sufficient time for rest and let your mind wander from time to time.

Four Hour Days – The Revolution We Need

In a world where 80–90 hour weeks are deemed as aspirational by some leaders, the chapter titled Four Hours is rebellious. And is backed by science rather than grandiose statements of nation-building ambition. In other words, it is actually verifiable that the theory works and not propaganda.

Pang shows—through research and real schedules—that many high achievers across disciplines worked about four deeply focused hours a day, punctuated by real rest. This pattern isn’t limited to artists or tenured geniuses with full autonomy of their schedules. It appears among students who later become leaders in their fields.

The names in this chapter are hugely famous and their routines will shake your traditional beliefs on number of hours at work.

In a nutshell, if what you do is a demanding job, then it definitely requires imagination and adaptability— and both those qualities are restored not by pushing harder, but by taking deep naps, long walks, exercising vigorously, and practising genuine disengagement.

The Power of Deep Play

The final (and huge) insight that this book gave me is the reframing of what ‘rest’ really means. I didn’t realize it, but resting to me meant taking a nap or reading.

And I always thought of writing or creating something or debating an idea as ‘a hobby’, not rest. So why is it that engaging in these hobbies somehow restores my energies? It gives me a boost that is almost the same as a good run or a heavy exercise routine.

A similarly good feeling is completing the household to-do list of the week, a minor accomplishment but a disproportionate sense of satisfaction.

This is because, all of the above actually qualify as ‘rest’. The activities allow what anthropologists call deep play — activities that are intrinsically rewarding yet deeply meaningful.

“Ben Kazez’s description of app development and musical performance as requiring collaboration with smart people, interacting with audiences, and making choices.. (sometimes providing) a living connection to the players past.. building on things the player did in their childhood…” are all examples of deep play.

Deep play can restore something work alone cannot and can sometimes “acquire momentum, pulling its players in directions they never expected to go.”

Thomas Jefferson once wrote:

“It is neither wealth nor splendor, but tranquility and occupation, which give happiness.”

As I step into 2026, I’m carrying this with me: rest is not a reward for finishing life—it’s part of how meaningful work becomes possible at all.

And that may be the most productive idea I’m taking into the new year.

Thank you for reading with me through this year of books, ideas, and reflection.

I hope to keep bringing more of these to you in 2026 and beyond.

Best,

Ruta