Gang Leader for a Day — A book about ‘Character’

Every so often you encounter a book that refuses to stay confined to its subject matter. It spills over into your own life, your assumptions, your blind spots. Gang Leader for a Day by Sudhir Venkatesh is one of those rare books. It claims to be about American poverty and gangs, yet somehow it ends up being about something much less academic and much more personal: character—in all its messy, compromised, contradictory forms.

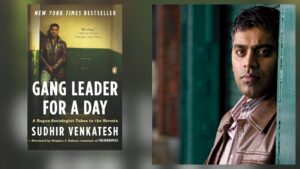

Gang Leader For A Day

~ Sudhir Venkatesh ~

Sudhir Venkatesh is a professor of Sociology at Columbia University. He has written extensively about American poverty and his writings, stories and documentaries have appeared in numerous well renowned publications.

This book tells the story of his early research in an unforgettable manner. While names have been changed, all the people, places and institutions mentioned in the book are real.

Sudhir enters the story as a first-year sociology graduate student at the University of Chicago in 1989, armed with multiple-choice surveys and a budding frustration with a discipline obsessed with numbers. The standard sociological recipe at the time was clear: collect data, run regressions, publish papers. But Sudhir, almost accidentally, chooses a different method.

“My frustration with the more scientific branch of sociology hadn’t really coalesced yet. But I knew that I wanted to do something other than sit in a classroom all day and talk mathematics.”

He walks into one of Chicago’s most notorious housing projects—Robert Taylor Homes—hoping for a few survey respondents. Instead, he finds J.T., a gang leader who rewrites his entire understanding of research, morality, and perhaps even friendship.

“Why don’t you just talk with people?”

J.T.’s first challenge to Sudhir is simple. Why the survey? Why the boxes? Why not just hang out and learn how people actually live?

What begins as an awkward encounter becomes a decade-long immersion into a world Sudhir had probably planned to analyze from afar. And this is where the book surprised me: it isn’t merely a sociological exposé. It is an emotional memoir of two men trying to understand each other within the limits—and the illusions—of their own contexts.

Sudhir describes growing up in affluent Southern California with a near religious faith in American institutions, especially the police. That faith dissolves quickly as he begins witnessing the stark reality of the projects:

“The buildings clustered tightly together but set apart from the rest of the city, as if they were toxic….. The police were unwilling to provide protection until tenants curbed their criminality.”

Sudhir’s early naïveté is not mocked in the book; it is dismantled gently, painfully, and through real, lived experience.

A Different Kind of Community

No matter the sheer scale of criminal activities described in the book, somehow it never paints the projects as a one-dimensional ‘danger zone’. The gangs, the drugs, the violence—they exist, of course. Yet woven into that fabric are threads of loyalty, absurdity, hope, and sometimes shocking moral negotiation – which somehow feels inevitable.

Sudhir sees an unexpected truth: that the gang offers him protection. And for many men, the projects offer the only semblance of opportunity they know.

“Strangely, while most people think of a gang as a threat, for me – an uninitiated person in the projects – the gang represented security.”

Then there are characters like Autry Harrison— a man who served in the army and returned to play the role of a community mentor—a path that very few people of his generation would choose to take. Autry runs a club for the youth and there are parts in the book where his presence seems to challenge the idea that this world is beyond redemption.

“He (Autry) and other staff members worked with school authorities, social workers and police officers to informally mediate all kinds of problems, rather than ushering young men-and women into the criminal justice system.”

The Boys & Girls Club becomes a quiet sanctuary where elderly folks play cards and pastors end up mediating gang disputes.

“Perhaps the very strangest thing was how sanguine the community leaders were about the fact that these men sold crack cocaine for a living.”

The book forces you to confront a kind of moral ambiguity that is uncomfortable precisely because it feels logical in context. What is right, really, when the entire environment is built on structures that have already failed the people in it? And how does one retain hope?

Ambition, Survival, and the Unfairness of Life

The book is as much J.T.’s story as it is Sudhir’s.

The sketch of J.T.—intelligent, ambitious, strategic and deeply flawed—is perhaps the most memorable aspect of the book. He wants recognition, not for criminal exploits, but for being good at the role life forced on him. In fact, Sudhir states clearly that J.T. provides access and protection to him believing that Sudhir is actually researching so he can someday write a book on J.T.’s life. It is this attention that J.T. craves and enjoys – and it is a belief that Sudhir allows to deepen even though he knows that the purpose of his research is completely different. He never explicitly tells J.T. that he has no intention of writing a book on him.

“More than anything, J.T. was desperate to be recognized as something other than just a criminal.”

There is something tragically universal about that desire.

Even Sudhir finds himself questioning what “good work” means. He grows angry at the academic world for its detachment, yet he also grows complicit in the very exploitation he thinks he is avoiding. The author’s very vulnerable reflections show his state of mind, how deeply the circumstances he witnesses affect him and the loneliness that follows.

“I found that I was angry at the entire field of social science.. It struck me as only partially helpful to convince youth to stay in school : What was the value in giving kids low paying menial jobs when they could probably be making more money on the streets?.. I felt as though the other scholars were living in a bubble, but my arrogant tone did little to help anyone hear what I was trying to say. I worried that my behavior might embarrass Wilson (Sudhir’s professor), but I was too bitter to take a moderate stance. I was growing quieter and more solitary.”

In his desire to make his dissertation stand out with nuanced and solid data, Sudhir ends up making a mistake – he shares financial information that tenants have shared with him in confidence – and he shares it with the two people that have the power to exploit that the most. This eventually forces him into uncomfortable introspection.

C-Note, a gang member, asks him the question that becomes the emotional spine of the book:

“You need to think about why you’re doing your work.”

Loneliness, Guilt, and the Limits of Understanding

I was unexpectedly moved by Sudhir’s vulnerability. Not scholarly vulnerability—the kind you polish into a dissertation—but real human vulnerability. When Sudhir leaves for Harvard and later Columbia, the relationship with J.T. begins to fray. J.T. grows nostalgic; Sudhir grows evasive. It’s a very human unraveling—two people who met under unlikely circumstances now drifting apart under predictable ones.

While they never explicitly talk about it, at this stage, J.T. has probably figured out that Sudhir has no intentions of writing a book on him. Even then, J.T. reaches out to Sudhir offering him a contact and access to another gang leader so Sudhir can continue his research in New York. This meeting is brief and J.T. brings a short letter to hand over. The letter is worn at the creases, and simply reads:

“Billy, Sudhir is coming out your way. Take care of the nigger… He’s with me.”

It’s crude. It’s affectionate. It’s protective. It is everything the book is—morally tangled and emotionally honest.

So What Is Good Character?

The book left me sitting with this question longer than I expected.

Is good character moral purity?

Is it loyalty? Is it resilience and survival?

Is it the courage to acknowledge complexity where others prefer clean narratives?

Maybe character is simply what remains once our roles—student, gang leader, tenant leader, researcher, anything else —are all stripped away. Maybe it’s the small choices we make in impossible situations. Maybe it’s the flawed, earnest attempt to do right when right is unclear.

What Gang Leader for a Day ultimately reveals is not the sociology of gangs, nor the policy challenges of a country, but the quiet truth that people—wherever they are—are more complicated than their circumstances.

Why do you do what you do?

Best,

Ruta