“The post-pandemic workplace is fluid, unsure, and ideal for workers with a breadth of knowledge and skills.”

Range is a delightful book. It is quite like a science paper in the sense that it heavily relies on research and case studies to make observations. It can also be quite therapeutic if you have the FOMO because of a lack of deep specialization professionally.

The author is David Epstein, 42, graduate of Columbia University. He has master’s degree in environmental science and journalism. And I love the title “Range” for this #1 NY Times Bestseller.

Range provides incredible insights into “How Generalists triumph in a Specialized World” and why. This book should be a mandatory read for all parents and people leaders especially in large corporations. If you think about it, the required navigation skills are somewhat similar for parents & corporate leaders – dealing with uncertainty, responsibility for end outcomes of other people, coaching, cultivating discipline but with empathy, active listening..

I really enjoyed this book and here is why.

Growing up, I was always a bit self-conscious about ‘not being inclined to specialization’. I just found it incredibly boring to go deep into one topic – and thanks to teachers & professors – I concluded that I was ‘reasonably bright but tend to get distracted easily’.

This backdrop pretty much defines my academic profile – it is quite unimpressive – there are no marks awarded for arguing with teachers! The on-the-job type of learning however was enjoyable, thankfully. I can tell you that I have asked ‘ridiculous questions’ at work – and have had mixed results. Sometimes, shocking people with my lack of understanding, and sometimes shocking them at how little they really know. In every scenario though, I have ended up wiser and sometimes the entire group has ended up wiser. Asking good questions is perhaps the most underrated skill.

So you can imagine my surprise when I started to do well enough to be on panels where people ask me ‘what is your mantra?’. Honestly, I had no idea and so I started to think about it. A bias for action and being energized by different types of problems meant that my managers liked ‘throwing things at me’ with the hope that ‘usually it will get done or at least we will fail fast!’.

It is only in my late 30’s that I came across the term lateral thinking. Because I didn’t have deep specialization, I was ‘not encumbered by models and frameworks of how to think’. Also, because I didn’t have deep specialization, all sorts of problems came to me that ‘didn’t quite fit under an umbrella’. A tendency to ‘not always stay in my lane’ and a ‘higher risk appetite’ could also have some role to play in the journey so far, professionally..

(P.S.: it might amuse you to know that all text in a single quote is feedback I have received over the years verbatim!)

And yet, I often come across situations where I see generalists being undervalued. This book therefore was quite helpful for the questions that thus far had remained unanswered in understanding why – and not taking it personally ;).

“Despite the demand for generalists, most feel unsupported..some generalists feel it’s easier to see the goals and accomplishments of specialists, because their roles are more defined and specific.”

Roger vs Tiger

David E. starts with stories from sport. “Roger vs. Tiger” explores the journey of two legendary athletes. One who started to specialize before he could learn how to talk and one who did much later. I’ll let you read the book to find out who did what. The fact that two different paths lead to somewhat similar levels of success in individual sport makes for an interesting opening.

These patterns of the desire for early & continued specialization extend beyond the sporting world. David E. takes the reader through this thought process and some of it’s perilous outcomes.

“We are often taught that the more competitive and complicated the world gets, the more specialized we all must become…..and each specialized group sees a smaller and smaller part of a large puzzle..

(for e.g.) Legions of specialized groups optimizing risk for their own tiny pieces of the big picture created a catastrophic whole..(2008 financial crisis).

Highly specialized heath care professionals have developed their own versions of the ‘if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail’ problem..(cardiologists treating chest pain with stents)”

And so even before you get officially to Chapter 1 of the book, David E. provides compelling arguments on why people who start broad and embrace diverse perspectives as they progress, tend to succeed particularly in uncertain or as he calls them – wicked learning environments.

Do specialists get better with experience or not?

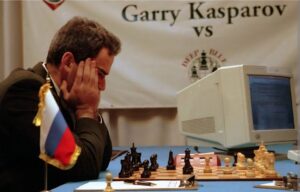

If you don’t read any other chapters, do read this one – even if you don’t play chess!

“Psychologist Gary Klein has shown that experts in an array of fields are remarkably similar to chess masters in that they instinctively recognize familiar patterns. One of Klein’s colleagues, psychologist Daniel Kahneman…probed the judgements of highly trained experts, he often found that experience had not helped at all. Even worse, it frequently bred confidence but not skill.”

Gary Kasparov, Chess Grandmaster famously lost against the computer Deep Blue.

“Anything we can do, and we know how to do it, machines will do it better.” The Machine could learn millions of combinations and get ahead with tactics therefore obviating human experience of seeing and recognizing those patterns almost in seconds. But strategy – that, it could not do.

“Human creativity was even more paramount under these circumstances, not less….Our greatest strength is the exact opposite of narrow specialization. It is the ability to integrate broadly.”

From chess grandmasters to revered musicians to legendary artists, David E. has some stories that will shock you on the background and thought process of very successful people – and how a very varied experience is actually at the heart of their success. Their ability to think freely allows them to solve for problems very differently – often seeing a solution precisely because they don’t have too much experience to be blindsided by it.

“Breadth of training predicts breadth of transfer…Learners become better at applying their knowledge to a situation they’ve never seen before, which is the essence of creativity.”

We would all agree with Adam Grant, that creativity is hard to nurture, but very easy to thwart. And that is one of the reasons why efforts have to be made in companies to ‘generate ideas’, a seemingly natural process if you think about it. It is also why we tend to ask a 3 year old to color the sky in blue.

Building the ability to think outside experience is key and does not happen entirely on it’s own. It could happen, with a lot of luck – but intentional efforts would reduce that dependency.

Psychologist Dedre Gentner, “In my opinion, our ability to think relationally is one of the reasons we’re running the planet. Relations are really hard for other species.”

Flirting with your possible selves

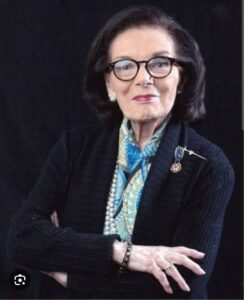

I think I found a role model in this chapter – Frances Hesselbein.

Her career may have started in her midfifties, but became extraordinary! However, the meandering path that got her there is the real story. Some undefinable process of digestion occurred as diverse experiences accumulated in her life.

“I did not intend to become a leader, I just learned by doing what was needed at the time.”

Frances Hesselbein never graduated from college, but her office has 23 honorary doctorates.

There is a real argument for short-term planning here. “Here’s who I am at the moment, here are my motivations, here’s what I’ve found I like to do, here’s what I’d like to learn, and here are the opportunities. Which of these is the best match right now?”

David E. calls it “match-quality”. An opportunity that is right for your particular version of self at a time. That combination can create magic, solve complex problems that haven’t been cracked by teams of specialists and basically just catapult you to another level. Only if you are open-minded that is. Only if you are willing to expand your range.

“Instead of working back from a goal, work forward from promising situations. This is what most successful people do anyway.”

Discovering who you are and what your ‘match-quality’ is professionally can be a lengthy process – but it doesn’t need to be dull. There are many roads to the summit of any mountain. And there are many mountains.

“Career goals that once felt safe and certain can appear ludicrous, to use Darwin’s adjective, when examined in the light of more self knowledge. Our work preferences and our life preferences do not stay the same, because we do not stay the same”.

Moral of the story – Don’t undermine a generalist. They’ve beaten grandmasters, composed some unimaginable symphonies and discovered genes that experts couldn’t. And if you are a generalist, congratulations and good luck with the next problem 🙂

Ruta